SAVE THE DATE FOR IFPAC-2026! Network and share your knowledge on advancements in manufacturing science. Join Brian Rohrback for the following presentations.

SAVE THE DATE FOR IFPAC-2026! Network and share your knowledge on advancements in manufacturing science. Join Brian Rohrback for the following presentations.

Chemometrics in Chromato-Context (ID# 83)

Chromatography is one of the most useful technologies to employ for routine chemical assessment in industry. In many cases, it is the cheapest and most adaptable technology available to fully document the composition of our samples. Chemometrics has been used to interpret chromatographic traces, although the implementation has been far less than seen in spectroscopic applications. It gives us the chance to review where chemometrics has been utilized in the chromatographic sciences and where the advantages lie. Starting with the chromatography basics, this presentation builds up the world of chemometrics step-by-step to show where the technology has been used and can contribute in the form of driving much more reliable results from the data we collect.

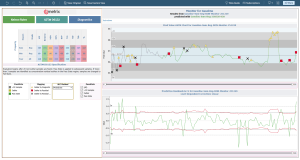

Fully Integrated Data Analysis (ID# 84)

We employ many sources of analytical information to perform quality control on the processes we manage. In many cases, we are not utilizing the information content from the data we currently collect. In most quality control situations, results from different sources will need to be merged into a single release metric. This can be done hierarchically, where information will need to be factored in order of priority or response time. Another option is to process simultaneous data in a blended, data fusion model. Care must be taken to ensure that the complexity of fusing several sources of data does not involve so much complexity that the system is unwieldy or simply cannot be used. Here we will discuss current techniques and show how the value of the information stream can be improved by more timely integrated data analysis. An example from the pharmaceutical classification of botanicals shows the power of this approach.

Chemometrics – COPA (Chemometrics for Online Process Analysis)

Chairs: Brian Rohrback, Infometrix, Antonio Benedetti, Polymodelshub, and Hossein Hamedi, Arrantabio

Chemometrics is central to all calibration work in spectroscopy and has influence in most of the instrumentation tied to product quality control. We are investigating the challenges and the successes tied to the implementation of chemometric technology as it relates to the process industry, whether for pharmaceuticals, for consumer products, for food, or for chemicals. We seek to optimize quality control.

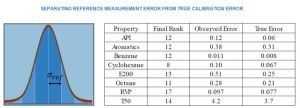

Globalized Spectroscopy (ID#261)

Implementing spectroscopy applications is often a complex management process, even if the deployment is restricted to a single spectrometer. When a company wants to roll out spectroscopy in multiple locations additional potential problems arise however, managed properly, the benefits are significant. IR, NIR, and Raman are the most common optical systems employed to measure chemistry in a quality control application, but they require a calibration to convert spectral signatures to the properties of interest. Unless an objective mechanism for performing calibration is available across the sites, product quality results will vary. It is possible to package “best practices” into a system that forces consistency and optimal outcome. By removing the subjective nature of manual calibrations, the quality of the quality control can be assessed and maintained at a high level.

View the program preview here.

Contact info@infometrix.com for questions or for more information on presentations and event details.

Speed Dating Chemometrics and Machine Learning

Speed Dating Chemometrics and Machine Learning